Prawn farming goes digital

Jessica Guttridge

Aquaculture is undergoing a transformation globally, but there’s a substantial gap between how much is harvested and how much could be

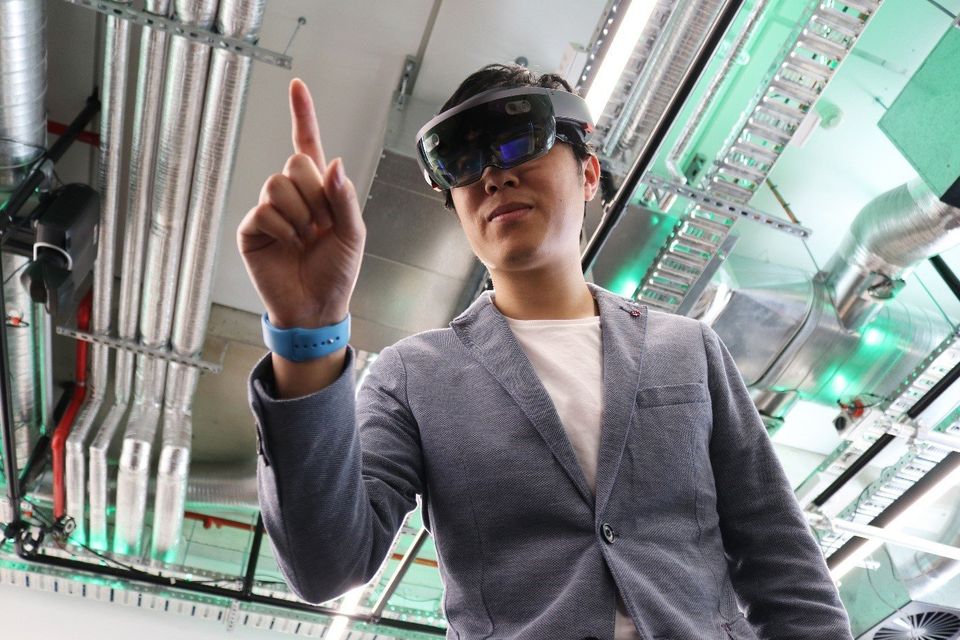

CSIRO researchers are using augmented reality, sensor technology and next generation data interaction to help inform prawn farmers’ decisions, increasing their yield.

By combining wearable goggles with water quality information already being collected, farmers can look at the pools of water and instantly see the vital information they need, with the information ‘augmented’ on top of reality as an overlay.

In real-time, farmers can monitor water quality parameters like dissolved oxygen and pH levels simply by looking at the tanks, and interact with the information using hand gestures.

The technology was developed by CSIRO’s Digiscape

Future Science Platform using the power of Data61’s data monitoring and analysis platform Senaps.

The technology is wearable and hands-free, so farmers can access it while they’re walking around and managing the prawn ponds.

In an interview with Innovation Intelligence, the project leader, Dr Mingzi Xi, discussed how the technology could change aquaculture.

“There’s a significant delay between when the data is captured and when the decision is made, and the prawn ponds are a dynamic environment. In two hours, the conditions can change from optimal situation to a threatening situation, and if you can’t make an informed decision in a timely matter that can potentially be a great financial loss.”

Water quality is an important constant concern for prawn farmers, as prawn ponds often gather nutrients, bacterial and algal growth from excess feed and waste from the prawns themselves which can produce ammonia, and lower oxygen levels at night.

“Prawn farmers tell us that they don’t actually farm prawns, they farm water quality,” Dr Xi said.

Water quality monitoring is labour intensive, with significant delays between the measurements and being able to see important trends in the data.

“The majority of prawn farming or aquaculture is quite labour intensive, partly because of the harsh environment. They must use a handheld floating device which gives them the most accurate results, measure water conditions, and then record the data, and they must do this across the entire farm. Sometimes this can be six hours, then they bring this back to the office, and then the decision maker is able to make a decision.”

“This could give them the information they need to better manage animal health and feed inputs, for example, and even share the visuals in real time with managers in the office or external experts for fast input,” Dr Xi said.

The initial run for the project is three years, with the researchers already being about 19 months in. CSIRO has chosen prawn farming as the first agricultural industry to test this technology, with plans to expand into other sectors shortly.

“We’ve started with aquaculture, and afterwards if we’re successful, we’re planning to introduce it to more broader agriculture industry like sugar cane farms.”

“We can see this technology becoming a normal part of farm operations no matter what you farm, as all types of farming become more reliant on gathering and understanding data from sensor technologies,” Dr Xi said.

While the Australian prawn industry is one of the smaller producers in volume in the world, it leads the world in productivity with an average yield of more than 9,000 kg per hectare, according to Australian Prawn Farmers Association (APFA) 2015 report.

In the same report APFA said the Australian prawn farming industry produces in excess of 5,000 tonnes of product annually with a farm gate value estimated to be $87.7 million, providing more than 300 direct jobs.

“We saw there was a need in an industry that is growing very quickly, and there wasn’t enough workforce to support them. This project is about looking into how to help them succeed using artificial intelligence to understand data and how to deliver the projects the right way.”

“As long as humans are involved in the decision making process, this technology can help. We don’t make decisions on behalf of the decision makers, we deliver the information that they need most to make better decisions.”

Prawn farms are currently located in two Australian states; New South Wales and Queensland.

Pacific Reef Fisheries Pty Ltd, a prawn farm operator in northern Queensland, is working with CSIRO to provide real world conditions for testing the system. Dr Xi said that they plan to start their first farm trial there in a few weeks.

Kristian Mulholland, Environmental Manager of the farm said augmented reality had the potential to transform productivity in the aquaculture industry.

“Augmented reality technology could be a huge game changer for our industry to make water quality monitoring so much quicker and easier, all in real time, and bringing a visual aspect of data display to efficiently make more accurate management decisions,” he said.

In 2016 I published a blog article titled Moonshots for Australia: 7 For Now. It’s one of many I have posted on business and innovation in Australia. In that book, I highlighted a number of Industries of the Future among a number of proposed Moonshots. I self-published a book, Innovation in Australia – Creating prosperity for future generations, in 2019, with a follow-up COVID edition in 2020. There is no doubt COVID is causing massive disruption. Prior to COVID, there was little conversation about National Sovereignty or supply chains. Even now, these topics are fading, and we remain preoccupied with productivity and jobs! My motivation for this writing has been the absence of a coherent narrative for Australia’s business future. Over the past six years, little has changed. The Australian ‘psyche’ regarding our political and business systems is programmed to avoid taking a long-term perspective. The short-term nature of Government (3 to 4-year terms), the short-term horizon of the business system (driven by shareholder value), the media culture (infotainment and ‘gotcha’ games), the general Australian population’s cynical perspective and a preoccupation with a lifestyle all create a malaise of strategic thinking and conversation. Ultimately, it leads to a leadership vacuum at all levels. In recent years we have seen the leadership of some of our significant institutions failing to live up to the most basic standards, with Royal Commissions, Inquiries and investigations consuming excessive time and resources. · Catholic Church and other religious bodies · Trade Unions · Banks (and businesses generally, take casinos, for example) · the Australian Defence Force · the Australian cricket teams · our elected representatives and the staff of Parliament House As they say, “A fish rots from the head!” At best, the leadership behaviour in those institutions could be described as unethical and, at worst….just bankrupt! In the last decade, politicians have led us through a game of “leadership by musical chairs” – although, for now, it has stabilised. However, there is still an absence of a coherent narrative about business and wealth creation. It is a challenge. One attempt to provide such a narrative has been the Intergenerational Reports produced by our federal Government every few years since 2002. The shortcomings of the latest Intergenerational Report Each Intergenerational Report examines the long-term sustainability of current government policies and how demographic, technological, and other structural trends may affect the economy and the budget over the next 40 years. The fifth and most recent Intergenerational Report released in 2021 (preceded by Reports in 2002, 2007, 2010 and 2015) provides a narrative about Australia’s future – in essence, it is an extension of the status quo. The Report also highlights three key insights: 1. First, our population is growing slower and ageing faster than expected. 2. The Australian economy will continue to grow, but slower than previously thought. 3. While Australia’s debt is sustainable and low by international standards, the ageing of our population will pressure revenue and expenditure. However, its release came and went with a whimper. The recent Summit on (what was it, Jobs and Skills and productivity?) also seems to have made the difference of a ‘snowflake’ in hell in terms of identifying our long-term challenges and growth industries. Let’s look back to see how we got here and what we can learn. Australia over the last 40 years During Australia’s last period of significant economic reform (the late 1980s and early 1990s), there was a positive attempt at building an inclusive national narrative between Government and business. Multiple documents were published, including: · Australia Reconstructed (1987) – ACTU · Enterprise Bargaining a Better Way of Working (1989) – Business Council of Australia · Innovation in Australia (1991) – Boston Consulting Group · Australia 2010: Creating the Future Australia (1993) – Business Council of Australia · and others. There were workshops, consultations with industry leaders, and conferences across industries to pursue a national microeconomic reform agenda. Remember these concepts? · global competitiveness · benchmarking · best practice · award restructuring and enterprising bargaining · training, management education and multiskilling. This agenda was at the heart of the business conversation. During that time, the Government encouraged high levels of engagement with stakeholders. As a result, I worked with a small group of training professionals to contribute to the debate. Our contribution included events and publications over several years, including What Dawkins, Kelty and Howard All Agree On – Human Resources Strategies for Our Nation (published by the Australian Institute of Training and Development). Unfortunately, these long-term strategic discussions are nowhere near as prevalent among Government and industry today. The 1980s and 1990s were a time of radical change in Australia. It included: · floating the $A · deregulation · award restructuring · lowering/abolishing tariffs · Corporatisation and Commercialisation Ross Garnaut posits that the reforms enabled Australia to lead the developed world in productivity growth – given that it had spent most of the 20th century at the bottom of the developed country league table. However, in his work, The Great Reset, Garnaut says that over the next 20 years, our growth was attributable to the China mining boom, and from there, we settled into “The DOG days” – Australia moved to the back of a slow-moving pack! One unintended consequence of opening our economy to the world is the emasculation of the Australian manufacturing base. The manic pursuit of increased efficiency, lower costs, and shareholder value meant much of the labour-intensive work was outsourced. Manufacturing is now less than 6% of our GDP , less than half of what it was 30 years ago!