Wit, War and Words of ConscienceBy Helen Verity Hewitt

Wit, War and Words of Conscience

By Helen Verity Hewitt

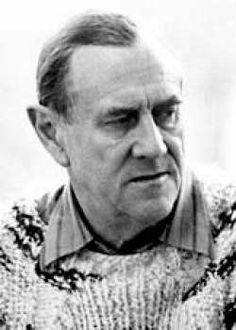

Patrick White

1912-1990

Novel Prize in Literature 1973

Self-doubt, staunch loyalty and violent rages are just some of the qualities that characterised Australia's only Nobel Laureate in Literature.

Self-doubt, staunch loyalty and violent rages are just some of the qualities that characterised Australia's only Nobel Laureate in Literature.

One of Patrick White's duties as a Royal Air Force (RAF) intelligence officer during World War 1 was to rifle through the pockets of the dead enemy for maps, letters, diaries, or all scraps of information. German pilots, ltalian soldiers, “the yellow flesh melting like butter into the sand and saltbush the corpses washed up by the sea were the worst'', he wrote in his autobiography Another of White’s duties was to censor the letters the airmen wrote. He became obsessed with the role. He was a young writer plunged into the most extreme human circumstances, death at his elbow, privy to the most private longings and despairs of his fellows in their communication to their loved ones. Literature and art were stays to him. During the inevitable periods of tedium and waiting, he read the Bible from cover to cover and all of Charles Dickens' novels. Of Dickens, he said: "As blood flowed, and coagulated in supporating wounds, as aircraft were brought down in flames and corpses tipped into the lime-pits of Europe, I saw Dikens as the pulse, the intact jugular vein of a life which must continue, regardless of the destructive forces which Dickens himself recognised.”

Goya, one of White’s favourite artists, had recorded his series The Disasters of War, all the scenes White was now witnessing. Goya’s passion, in which the cruellest human behaviour is depicted together with the most sublime, was also to be White’s passion. At the same time, The ultra-sensitve White was noting: “The background of trivialities, tantrums, adulteries, service feuds and wrangling for posting and perquisites, against which a great war is fought.”

His acute ear for the colloquial makes him a master of dialogue. As a novelist, White tried to capture the whole huge web of human life in its complexity, contradictions and confusion.

THE EFFECTS OF WAR

Echoes of war sound through most of White's work. His first post-war novel, The Aunt's Story, is a turbulent portrait of Europe on the eve of war. The megalomaniac protagonist of his novel Voss had his source in Hitler, and had come into White's imagination while he was stationed in the Egyptian desert. During a year's posting in Palestine, White absorbed "something of the Hebrew archetype" which fed into his portrait of Himmelfarb, the refugee rabbi who is crucified in Riders in the Chariot. At the end of The Twyborn Affair, White's flamboyant alter ego, Edith Wharton, is killed in London by a bomb during the Blitz. His two pre-war novels, while accomplished, are of their time; White's post-war novels exist on another level, for all time. What he called "Hitler's War" changed everything. "In a green pork-pie hat and a black polo sweater", the young White had blossomed and revelled in 1930s London, entranced by the theatre, the art, and the deep cultural history of the great city. London meant intellectual, artistic, emotional and sexual liberation. He had escaped from an extremely privileged but conservative world in Australia. The large White family had made a pastoral fortune during the 19th century. A saying in the rich Hunter Valley region used to go: "The Whites and the Wrights and the not-quites". (The Wrights were the family of the poet Judith Wright.) White, born in 1912, was expected to go on the land after completing his upper class education at English boarding school, Cheltenham College, and at Cambridge, where he read German and French. He did spend a year jackarooing in the Monaro between school and Cambridge, but felt like a stranger in Australia. In his autobiography, Flaws in the Glass, White repeatedly described himself as a "cuckoo" in his family, a "changeling"; his mother accused him of being a "freak". White later said he and his mother could not live in the same hemisphere, although he wrote dutifully every week. Explosive family tensions are a major theme in all of White's novels. White never saw either of his parents working. His father had retired from the land at the age of 42 and agreed to fund White's ambition to be a writer in London. It was probably a relief to everyone. "An artist in the family was almost like a sodomite; if you had one you kept him in the dark." London also meant escape from his mother's persistent attempts to match him up with some suitable girl. White had known from an early age that he was homosexual. In 1936, White established himself in London, found marvellous mentors (and lovers), immersed himself in modernist art, tried his hand at writing for the friendships were forged at this time with the artists Roy de Maistre and Francis Bacon, among others. White's first novel, Happy Valley, was published in 1939 and his second, The Living and the Dead, was in the offing when Hitler invaded Poland. White felt he had to enlist: "A sense of duty always sounds priggish when put into words". In Flaws in the Glass he repeatedly plays down his war service, but about one third of the autobiography is devoted to those five years: years in which he wrote nothing. White accepted a commission in Air Force Intelligence and while waiting for a posting experienced the beginning of the Blitz. "The incredible bombs had begun falling," he later wrote. His reality was being blown up.

Explosive family tensions and misunderstandings are a major l theme in all of White's novels.

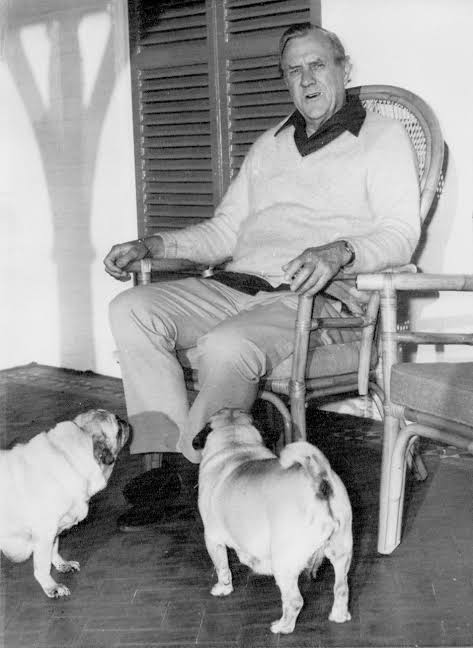

White's first posting was to the frontier between Eritrea and Sudan, then to Egypt, where he fell in love with the Mediterranean and Levantine melting pot of Alexandria. He was involved with the campaign that culminated in the relief of Tobruk. The Corps headquarters to which White was attached was cut off by German snipers. White, a very poor driver, had to steer a Dodge truck through the night, zigzagging through minefields reaching the ruins of Tobruk at dawn. In 1941, in Alexandria, White met Manoly Lascaris, a Greek Alexandrian who was to become "the central mandala" in his life. Their loving partnership was to last until White's death in 1990, despite White's self-confessed jealousy and violent rages. Lascaris' unshakeable Greek Orthodox faith was a stable point which attracted White, himself, always a restless spiritual seeker. White spent a year on duty in Athens following its liberation and became a lifelong Grecophile. The country's mix of mythology, history and physical beauty and the fatalistic, complex psychology of its people spoke to his own intense temperament. By 1948, White and Lascaris were living at Castle Hill, then seen as being outside Sydney. White's mother was now living in London. At a time when so many Australian artists and writers were becoming expatriates, White's decision to live and work in Australia was of vital importance to the development of Australian culture. Lascaris had wanted to leave Greece, and post-war London seemed like a graveyard to White. The Australian landscape drew him back, along with the flourishing art world that he discovered in Sydney and the plentiful food, in contrast with rationed London. "Anyone who has experienced hunger will remember a destroyer of the spirit even greater than lust," he recalls. Members of Lascaris' family had starved to death during the German occupation of Greece. Several years of despair following World War II gave way to a revived faith in a creative divinity. White's epic narrative, The Tree of Man, in which a lifetime of struggle ends with an affirmation of faith, was published in 1955. Deeply romantic by nature, White was a romantic modernist like many artists and writers whose work retained the mystic or transcendental strain of northern European romanticism, while fully absorbing the devastation of the two World Wars. Romantic modernism recognises the upheavals and horrors of the 20th century but clings to spiritual hope. Voss was published in 1957 to great acclaim; Riders in the Chariot, which coincided with, and contributed to, the high tide of visionary romantic modernism in Australia followed. This huge metaphysical novel envisages an Australia in which Aboriginal, Christian and Jewish mysticism meet and recognise one another.

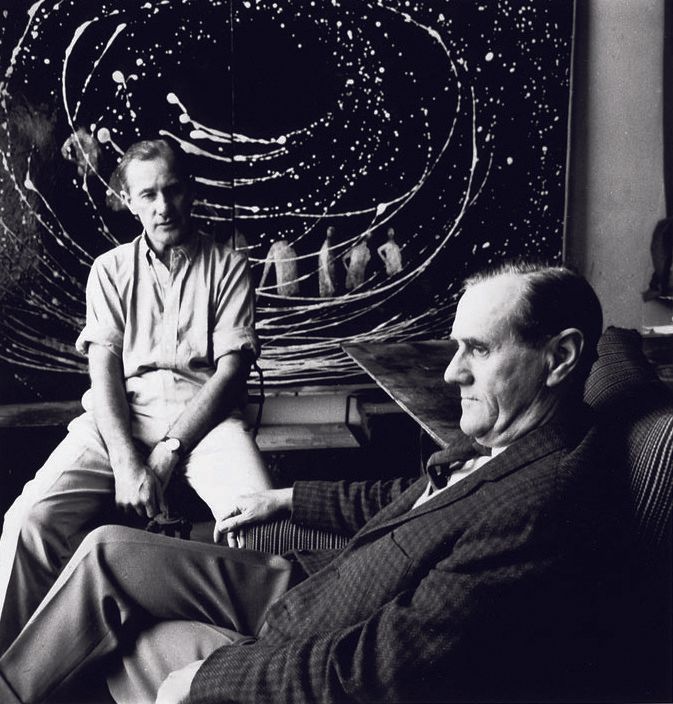

Published in 1961, Riders in the Chariot shows remarkable insight into the experience of Aboriginal children who were taken from their mothers. In the boyhood of his Aboriginal painter character Alf Dubbo, White evokes the double standard which turned a blind eye to white men fathering unacknowledged children with Aboriginal women. White outlines the assumptions that those children would be better off in white society; the children's vulnerability to abuse in their foster homes; and the passive powerlessness of the children, with no-one to trust or turn to. Dubbo's adulthood is an account of homelessness, alienation, loss of cultural identity, mental anguish, repeated betrayals by white society, alcohol abuse and early death through disease. White, in this novel, also expresses his contempt for the corrupting, contaminating effect of commercialism on Aboriginal creativity. White and Lascaris moved to Centennial Park in Sydney's exclusive eastern suburbs in 1964. In the big white house at Martin Road, White completed The Solid Mandala, and wrote The Vivisector, his portrait of a visual artist based on a number of artists he knew including Francis Bacon, Roy de Maistre and Sidney Nolan. Published in 1970, the novel was thought to be in the running for a Nobel Prize but it was apparently judged to be too bleak. White succeeded in winning the 1973 Nobel Prize for his next novel, The Eye of the Storm, about old age and revelation. A Fringe of Leaves, based on the historical events of a 19th century shipwreck off the Queensland coast, followed. White's last novels were The Twyborn Affair and Memoirs of Many in One. During the decades at Martin Road, White became one of Sydney's legendary figures with his looming, charismatic presence, his unmistakable voice unlike any other, his piercing gaze, his uncompromising forthrightness, his rages and the obvious intensity of his being. Only a strictly disciplined work regime allowed White to satisfy his need for solitude and silence, and his equally strong need for frequent trips back to Europe and for the creative stimulation and refreshing amusement to be found in the company of his fellow artists in any medium.

FALLING OUT

Many of his friends still missed his tart wit, his love of gossip and his generosity. Everyone wanted to know White but psychological vivisection by that scalpel eye was a danger. Victims included such old friends as comedian Barry Humphries, writer Geoffrey Dutton and Sidney Nolan. Nolan and White shared a dynamic friendship for more than 20 years. They were both passionate about Rimbaud, French modern painting and Greece. Both reinterpreted the history and mythology of the European explorers of Australia, sharing a feeling for their vulnerability, courage and arrogance. Nolan's paintings provide the landscape for Voss, the armature of A Fringe of Leaves, and significantly influenced The Vivisector and The Eye of the Storm. It was highly appropriate that Nolan accepted White's Nobel Prize on his behalf in Sweden in 1973. But White's beloved friend Cynthia, Nolan's wife, committed suicide in 1976 and the friendship between White and Nolan ran aground. White attacked the painter in Flaws in the Glass; Nolan responded with a savage homophobic painting of White and Lascaris. The ability to enter imaginatively into the psyches of his characters is White's forte. He himself felt fragmented, made up of many in one, able "to range through every variation of the human mind, to play so many roles in so many contradictory envelopes of flesh". Stage-struck from youth and his days as a "stagedoor Johnny" in London, White wrote plays as well as novels for the characters that inhabited his head. The best known include: The Ham Funeral; The Season at Sarsaparilla; A Cheery Soul; and Big Toys. Lascaris was always apprehensive about the writer's forays into the world of the theatre. White's temperament became particularly volatile in that exciting hothouse environment. He developed close working relationships and friendships with the theatre director Jim Sharman and popular actors including Kerry Walker and Kate Fitzpatrick. Everything was grist to White's mill. His own childhood reappears in many guises in his novels, in all its asthmatic, solitary angst and aspiration. The family drama is played over and over, with variations. The same four basic "sets" (two childhood homes, and the houses at Castle Hill and at Centennial Park) are rearranged to accommodate a multitude of scenarios. Overseas haunts, such as London and Greece, are also used. White asserted the characters in his books arose from his unconscious, all aspects of himself but also borrowed from neighbours, friend and foe, and whomever crossed his path. For example, many of the supporting cast in The Vivisector are recognisable characters in the Sydney art world. Characters belonging to Lascaris' extended, complicated family add to the throng. White's huge imaginative life never ceased; every night he dreamt vividly, and those dreams flowed into his writing. In addition to the plays and novels, White also wrote a number of short stories, most of which are collected in The Burnt Ones and The Cockatoos. He said he hated writing, but had no choice, that the novels forced their way out of him. In 1974, he opened the Henry Lawson Festival of Arts, held in Lawson's birthplace, Grenfell, New South Wales (NSW), and took the opportunity to reiterate his romantic understanding of the creative spirit. Lawson, he said of the famous writer and poet, was "a tortured manic depressive soul like many other artists.

I know this is an unfashionably romantic view of the creative artist, but I think the fashionable option has been developed largely by intellectuals with little of the artist in them." White once described himself as "a skeleton at the Australian feast". He raged against what he saw as Australian complacency, insularity, hypocrisy and materialism. "A pragmatic nation, we tend to confuse reality with surfaces. Perhaps this dedication to surface is why we are constantly fooled by the crooks who mostly govern us. "

PASSIONATE CRUSADER

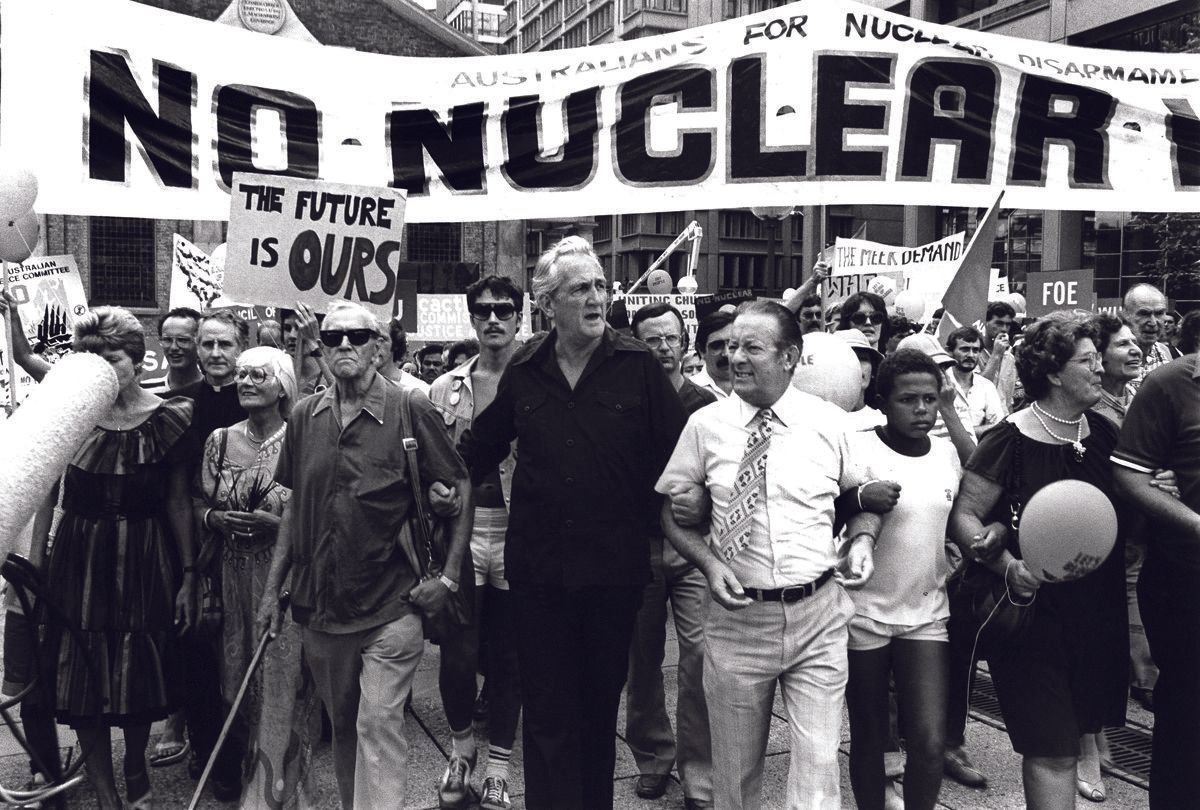

White devoted more and more time to political and environmental issues, although it took him away from his work. He was deeply involved with the battle to save Fraser Island, in south Queensland and the largest sand island in the world. He supported the Green Bans of Jack Mundey, the leader of the NSW Builders' Labourers Federation who led industrial actions to help protect some prominent Sydney buildings from over-development. He gave the keynote address at the inaugural meeting of People for Nuclear Disarmament and continued to be a frequent marcher and speaker at their rallies. _ White also gave much practical support to the Aboriginal Treaty Committee and to the Aboriginal Dance Theatre. In White's vision, there can be no true culture or "home" in Australia for non-indigenous Australians without reconciliation with the Aboriginal "spirit of the land" and the original inhabitants. He profoundly desired an Australian culture free of overwhelming British influence, in which there would be room for the voices of all comers - an expanding fusion and profusion of every-growing complexity and richness. White did everything he could to foster this development. He was a generous patron to young artists, and he gave some 250 works to the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Having won a number of literary prizes, he decided in 1967 to accept no more (in order to give other writers a go) and turned down the Miles Franklin and the $10,000 Britannica Award in that year. Suspicious of honours, he turned down a knighthood and, later, an Order of Australia. He did accept the Nobel Prize in 1973 but then used all the money to establish an annual literary award for older Australian writers who had not received their due recognition. White died in 1990 after a bronchial collapse following a lifetime of chronic asthma. In an epigraph to Patrick White Speaks, a 1989 collection of articles and public addresses by White, the poet and critic Dorothy Green expressed the feelings of many when she wrote: "What interests me most about this book is its consistency with the novels - the moral stance is firm from the beginning. "As novelist and citizen, Patrick White is the voice of our country's conscience. He begs us to search our hearts."

Vital Statistics:

Name: Patrick White

Born: London, England,

Birthdate: May 28 1912

Died: September 30 1990 in Sydney, Australia

School: Tudor House, a private school in NSW, Australia; Cheltenham College, England

University: Kings College, Cambridge

Partner: In 1941 White met Manoly Lascaris, with whom he lived until his death

Children: None

Lived: Mainly in Sydney

Awards and Accolades

1941: Gold Medal of the Australian Literature Society for Happy Valley

1957: WH Smith Award for Voss

1961: Miles Franklin Award for Riders in the Chariot

1965: Gold Medal of the Australian Literature Society for Riders in the Chariot

1973: Nobel Prize in Literature

1974: Australian of the Year

Novels

1939: Happy Valley

1941: The Living and the Dead

1948: The Aunt’s Story

1955: The Tree of Man

1957: Voss

1961: Riders in the Chariot

1966: The Solid Mandala

1970: The Vivisector

1973: The Eye of the Storm

1976: A Fringe of Leaves

1980: The Twyborn Affair

1986: Memoirs of Many in One

WHY HE WAS AWARDED THE NOBEL PRIZE

Patrick White was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1973 for his novel, The Eye of the Storm. In the presentation speech, the Swedish Academy said he won “for the epic and psychological narrative art which has introduced a new continent into literature”. The Eye of the Storm places an old, dying woman in the centre of a narrative which revolves around and encloses the whole of her environment. Past and present blur until we have come to share an entire life panorama, in which everyone is on a decisive dramatic footing with the old lady. Because of the Nobel Prize, Patrick Whites literary fame spread throughout the world.