A Quantum Leap

A Quantum Leap

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Prokhorov 1916 - 2002 Nobel Prize in Physics 1964

Shared with Charles Hard Townes and Nicolay Gennadiyevich Basov

Shared with Charles Hard Townes and Nicolay Gennadiyevich Basov

Laser applications, which range from supermarket checkouts to global communications and broadcasting networks, can be traced back to the work carried out by Aleksandr Mikhailovich Prokhorov. His work provided the first practical demonstration of quantum electronics, and the origin of today's vast industry for lasers. Other applications include high fidelity recording on compact discs, surgery, printing and astronomy and space research.

Laser applications, which range from supermarket checkouts to global communications and broadcasting networks, can be traced back to the work carried out by Aleksandr Mikhailovich Prokhorov. His work provided the first practical demonstration of quantum electronics, and the origin of today's vast industry for lasers. Other applications include high fidelity recording on compact discs, surgery, printing and astronomy and space research.

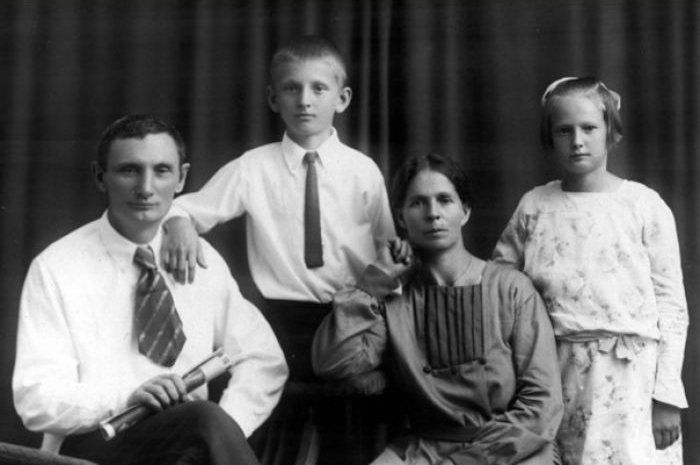

Aleksandr Mikhailovich Prokhorov was born in 1916 at the family farm in Russell Road, Peeramon in the Atherton Tablelands, Queensland. His Russian emigre parents, Mikhail Ivanovich Prokhorov and Mariya Ivanovna Mikhaelovna (Prokhorov) had fled from Siberia to Australia in 1911 because of Mikhail's involvement in revolutionary activities. As an opponent of the Tsarist regime, he had been sent to Siberia following the abortive 1905 revolution. After the hoarfrost, howling wolves, frozen mountains, salt mines and human chain gangs of Siberia, the young couple's new home in Australia's tropical far north was a world away, figuratively and literally. At the time, the Cairns district was actively attracting migrants from all over Europe to develop tin and gold mines, cut timber and work on the railways. Among the new arrivals looking for a fresh start were a small group of Russian families, many highly educated and, like the Prokhorovs, escaping the serious social upheavals taking place in their homeland. Looking for some sense of community, many took up new land selections in the same area of lush rainforest country characteristic of the Atherton Tablelands. This part of the world was colloquially known as Little Russia. As for Peeramon, little remains of its pioneering past. Today the town's main built attraction is Peeramon Hotel, one of the oldest pubs in Queensland. Prokhorov was the third and youngest child. His parents also had two daughters, Jane and Lila. When he was seven years old, Lila - the eldest sister - died unexpectedly. That same year, 1923, the family decided to return to Mother Russia, a move probably influenced by the propaganda filtering out of the country following the October Revolution of 1917. When the Communists took power in the country, they promised a worker's paradise, raising the hopes of many that the horrors visited on Europe by the World War I would be expunged by a new utopian world order.

LIFE UNDER STALIN

Life in Russia as a teenager was not easy for the young Prokhorov. The civil war had been a disaster for the country's economy, culminating in the enormous famine of 1920-21. The following year, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) was established and when Vladimir Lenin died soon after, his successor Joseph Stalin began his reign of terror. It was during this period that Stalin introduced farm collectivisation, effectively wiping out the peasantry both as a class and as a way of life. He also oversaw the execution or exile of millions to Siberian concentration camps. Against this bloody and turbulent background, Prokhorov grew into adolescence. In 1934, he was accepted into the Leningrad State University and graduated four years later with an honours degree in physics. This led to postgraduate work at the PN Lebedev Physical Institute, Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow.

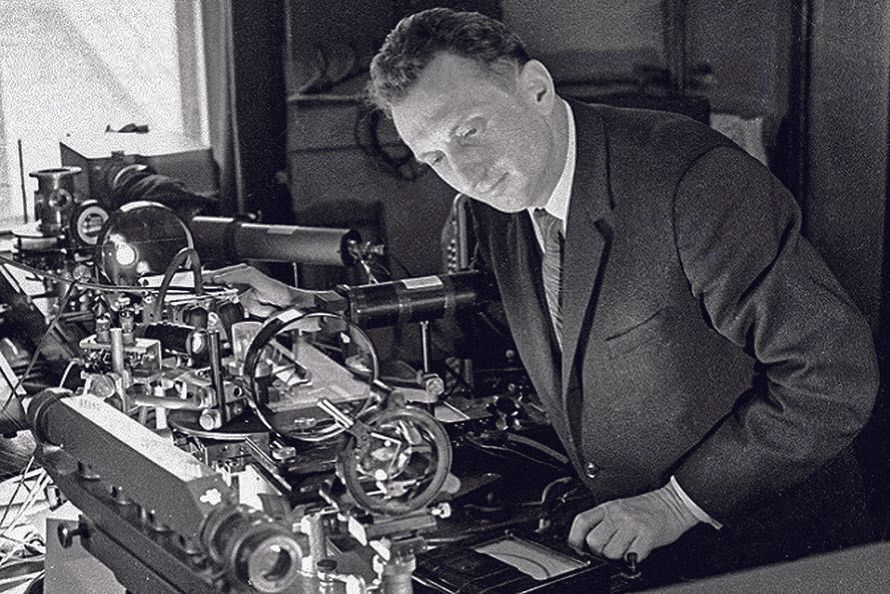

There he studied the propagation of radio waves over the earth's surface and with one of his research directors, the physicist VV Migulin, proposed a novel technique for using radio interference to explore the ionosphere, one of the layers of the upper atmosphere. In June 1941, the German invasion of Russia interrupted Prokhorov's studies and he entered military service, despite eligibility for exemption because of his academic research. In the same year, he married Galina Alekseyevna Shelepina, a geographer with whom he later had one son, Krill. However, instead of a life of simple domesticity with his new bride, Prokhorov went on to serve with the Red Army in a period of warfare that would eventually kill one-sixth of the population. The battles for Leningrad (Prokhorov's old stomping ground) and Stalingrad were particularly protracted and obscene. While defending his country, Prokhorov was wounded twice. After his second injury in 1944, he was demobilised. He was awarded the Order of the Patriotic War, 1st class, and the Medal for Valour for his bravery. After taking off his uniform, Prokhorov wasted no time in resuming his studies as a senior research associate in the Oscillations Laboratory of the PN Lebedev Physical Institute. His main passion by this time was nonlinear oscillations about which he devised a theory that became the subject of his thesis. This earned him his candidate's degree (equivalent to a master's degree) in 1946. For this work, he and two other physicists were awarded the Leonid I Mandelshtam prize named in honour of a Soviet radio physicist of considerable repute. From 1947, he studied the radiation from electrons produced in a synchrotron (a device that accelerates charged particles such as protons and electrons in widening circles to very high energies). He demonstrated that the electrons radiate at wavelengths of the order of centimetres in the microwave region. As a result of these investigations, he wrote his PhD thesis, Coherent Radiation of Electrons in the Synchrotron Accelerator, in 1951. The year before, Prokhorov was appointed assistant director of the Oscillations Laboratory at the PN Lebedev Physical Institute. In 1954, he was appointed head of the Institute, a post he held until his retirement. The Department of Oscillations soon became a research nursery. In 1959, the laboratory of radio astronomy was organised from one of the groups in the department, and in 1962 another specialist laboratory was dedicated to quantum physics. These days, the laser is taken for granted as a common component in domestic, industrial and scientific equipment. Yet for the first 10 years of its existence, it was regarded as a genius invention with little practical use. Its potential only began to emerge in 1964, when three scientists shared the Nobel Prize in Physics for its discovery. After completing his doctorate, Prokhorov began to investigate the question of radio spectroscopy on a wide scale. Somewhat later, he explored quantum electronics. To assist in this field of inquiry, he organised around him a team of young research scientists. Together they applied radar and radio broadcasting techniques, developed primarily in the United States and England during and after World War II, to study the vibrational and rotational spectra of molecules. Prokhorov focused his research on a class of molecules called asymmetric tops, which have three different rotational axes of symmetry and are the most difficult to analyse in terms of their rotational spectra. In addition to purely spectroscopic research, he carried out a theoretical analysis of the application of microwave absorption spectra to improving frequency and time standards. This latter work led to his collaboration with Nikolay Basov.

While the pair was searching for a technique to amplify microwave signals in spectroscopic experiments, they hit upon the idea of using a gas-filled cavity with reflectors at either end, in which the microwave beam would be intensified. They then discovered that this method produced microwaves with an extremely narrow range of frequencies. This laid the theoretical groundwork for the eventual construction of a molecular oscillator (or maser) operating on ammonia. This is a device emitting microwave radiation of a single wavelength, and was a precursor to the laser. In 1955, Prokhorov studied the electronic paramagnetic resonance spectra of ruby with AA Manenkov, which actually made it possible to suggest it as a material for lasers in 1957. The two announced the discovery of their molecular generator in a paper read before the All-Union Conference on Radio Spectroscopy held by the USSR Academy of Sciences in May 1952. However, they held off publishing their results for more than two years, by which time the American physicist Charles H Townes had built a working maser and published his conclusions in the journal, Physical Review. Prokhorov's research came from a combined understanding of the science of optics and radio engineering. In 1964, he won the Nobel Prize in Physics for discoveries leading to the development of the laser. He shared this with compatriot Basov, also at the PN Lebedev Physical Institute in Moscow, and Townes whose discoveries were made independently at Columbia University and Bell Telephone laboratories. "Many believed that we had gone crazy, that it was impossible," Prokhorov said in a television interview in 2001. "It was a brave step, because before that no-one had said it was possible to create a generator of optical range. Then it became a new, independent science - optics." The inventions were the first practical demonstration of quantum electronics.

TAKING A STAND

Prokhorov was regarded as a politically controversial figure by the West. In the 1950s, he established the Radio Spectroscopic Laboratory at the Nuclear Physics Research Institute of the Moscow State University, of which he became a full professor in 1957. The research institute was also a key contributor to the Soviet program to build a counter system to then United States president Ronald Reagan's plans for a Star Wars defence system- so-called because it would destroy ballistic missiles in space. But Prokhorov, who became a lifelong member of the Communist Party in 1950, was anything but a conformist in an era when expressing views that did not align with the Party's was both rare and dangerous. Even under strict government controls, he was known for his independent streak and outspokenness. As the editor-in-chief of the multi-volume reference book, the Great Soviet Encyclopaedia, a position he held from 1969 until 1978, Prokhorov ignored orders to have the dissident physicist Andrei Sakharov excluded from the encyclopaedia. Father of the Soviet hydrogen bomb, Sakharov later turned anti-war activist, winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1975. He was also one of the regime's most courageous critics, a defender of human rights and democracy. This act of defiance by Prokhorov might have sent him to exile in Siberia like his father before him, had he not been so highly respected. But ironically, in 1983, he was one of four Soviet scientists to criticise Sakharov, who argued that the US might have to match the Soviet Union in nuclear weapons before effective arms reduction negotiations could begin. In the previous year Prokhorov had been one of 97 Nobel Prize winners who called for a freeze on his country's development and deployment of nuclear weapons. Yet in 1984, he lent his name to what was seen as a Soviet propaganda campaign. Prokhorov was one of four Soviet Nobel Laureates to sign a letter to President Reagan on behalf of an imprisoned Native American political activist, Leonard Peltier. The letter, however, was perceived to be part of a Soviet ploy to deflect attention from Sakharov's hunger strike, staged on behalf of his wife who had been refused permission to travel to the West for treatment of a heart condition. In the political sphere, his fame grew even more when he refused a government invitation to become a deputy in the Soviet parliament, famously declaring, "I am not a politician. I am a scientist". Prokhorov continued to use his position to engage world leaders throughout his life. In 1999, he was one of several scientists to sign a letter to the presidents of the US and Russia urging them to work together to help Russia make the transition to a democratic country. That same year he was the chair of the Russian Committee for the Observance of the United Nations International Year of the Elder Person. Although Prokhorov could have easily rested on his laurels after he won the Nobel Prize, he went on to create various types of lasers. In later years, his work focused on fibre and integrated optics and the creation of optical communication systems. He also supervised research in microelectronics, plasma physics, controlled thermonuclear fusion and laser medicine. Between 1973 and 1981, he was chief of the Department of General Physics and Astronomy of the Institute of General Physics in Moscow. In 1981, he became director of the Natural Sciences Centre of the PN Lebedev Physical Institute and in 1983 he founded the General Physics Institute in Moscow, part of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and served as its director until 1988. He also served as editor-in-chief of Laser Physics, a bi-monthly international journal.

END OF AN ERA

Prokhorov was 85 when he died of pneumonia on January 8 2002 in his home in Moscow. Scientists and politicians worldwide mourned his death, saying it marked the end of an era for Russian science. Then Russian president Vladimir Putin said in an issued statement: "His name is linked to outstanding discoveries that in many ways defined 20th century civilisation". Yevgeny Dianov, head of the Fibre Optics Scientific Centre, told Russian television: "His independence allowed him to speak freely to the Soviet authorities." Meanwhile, the Russian winner of the 2000 Nobel Prize in Physics, Dr Zhores Alferov, said that his death was "a bitter loss for world scientists". Outside of Russia, Art Guenther of the University of New Mexico's Centre for High Technology Materials in Albuquerque, New Mexico, spoke glowing of Prokhorov as "a lifelong committed scientist, a consummate gentleman, a Russian patriot, and a global opticist. His contributions to quantum optics have formed the basis for much of today's photonics evolution and applications." He added he was always impressed with the "respect and adoration of the Russian scientific community for his leadership, contributions, and friendship. He will be sorely missed." After his death, television footage showed Prokhorov's desk stacked high with files and paperwork. His glasses lay on top of one of the piles, as if he had only just taken them off. The scientist did not own a computer, which he half-joked would "interfere with his thinking". Instead he preferred to laboriously handwrite all his notes on hundreds of scraps of paper which could still be seen littering his office. Prokhorov is buried in Moscow's Novodyevichy Cemetery, the final resting place of many prominent Soviet and Russian scientists, writers and composers. And lest we forget, on the other side of the world in Atherton, Queensland, there is a memorial plaque celebrating the achievements of Peeramon's most famous son.

Vital Statistics:

Name: Aleksandr Mikhailovich Prokhorov

Born: Peeramon, Queensland, Australia

Birthdate: July 11 1916

Died: January 8 2002 in Moscow

University: Leningrad State University; Institute of Physics, Academy of Sciences, both in the USSR

Married: Galina Alekseyevna Shelepina in 1941

Children: A son, Krill

Lived: Mainly in Russia

Awards and Accolades

1948: The Mandelstam Prize

1959: Lenin Prize

1964: Nobel Prize in Physics

1967: Honorary professorship from Delhi University

1969 & 1986: Named a Gold Star Hero of Socialist Labour – The USSR’s highest civilian award

1988: The Lomosonov Gold Medal for outstanding achievements in Physics

Prokhorov was also a member of many professional associations. He was elected a corresponding member of the Soviet Academy of Sciences in 1960, and became a full academician in 1966 and a member of its Presidium in 1970. He was an honorary member of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Optical Society of America. He also received the Order of Lenin; Order of the Patriotic War, 1st Class; and Medal of Valour for his bravery.

Why he was awarded the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prize in Physics 1964 was awarded to Prokhorov with Nikolay Gennadiyevich Basov, also of Russia, and Charles Hard Townes of the US for work in the field of quantum electronics.

The project that earned the three scientists their prize was a device that generated an intense beam of pure microwave radiation called a maser. This is an acronym for Microwave Amplification by Stimulated Emmision of Radiation. The same principles of quantum electronics were later applied to the generation of an intense bean of pure light; hence the word laser, which is an acronym for Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation.

Between 1950 and 1955, Prokhorov and Basov devised a way of exciting electrons in ammonia molecules into higher energy states. The electrons were then relaxed back to their original lower state; the transition was accompanied by a burst of pure microwave radiation (a photon). The idea was then refined to generate shorter wavelengths of light. Applications of the research can be found in products such as compact discs and modern surgery.

In awarding the 1964 Nobel Prize in Physics, the Nobel committee recognised the contributions of all three physicists. One half was awarded to Prokhorov and Basov and the other half to Townes “for fundamental work in the field of quantum electronics, which has led to the construction and amplifiers based on the maser-laser principle”.