Miracle mould

Miracle mould

Scientific breakthrough saw penicillin offered to Australian civilians first, then brought to the wider community

Scientific breakthrough saw penicillin offered to Australian civilians first, then brought to the wider community

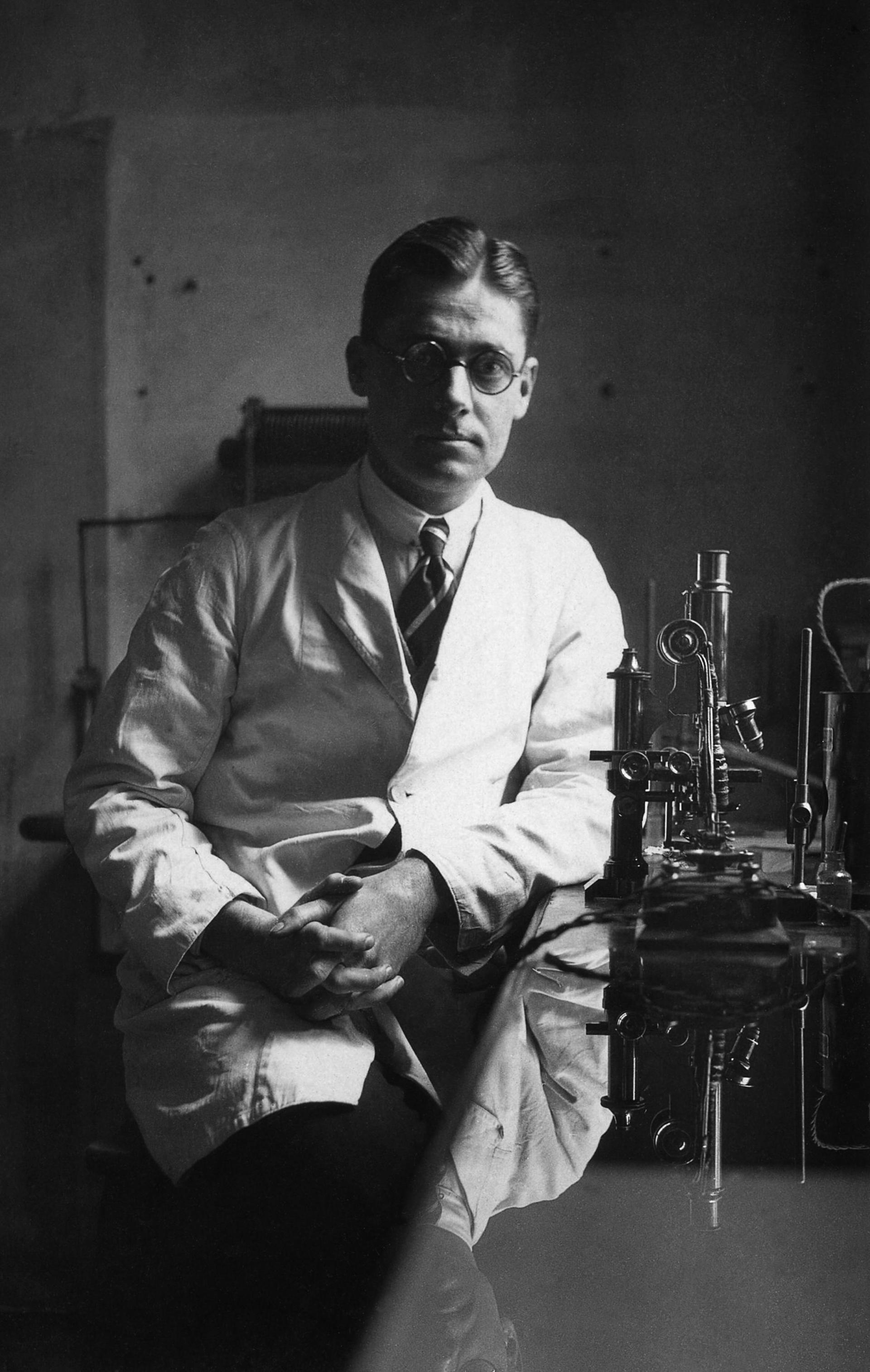

Howard Walter Florey 1898-1968 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine

For a man who was not thinking much about relieving hum.an suffering while he was experimenting with penicillin, Sir Howard Florey made one of the biggest contributions to the quest.

For a man who was not thinking much about relieving hum.an suffering while he was experimenting with penicillin, Sir Howard Florey made one of the biggest contributions to the quest.

Of all of Australia's Nobel Laureates, Howard Florey is undoubtedly the one whose work has provided humankind with the most profound benefits. Former prime minister Sir Robert Menzies once said Florey had more effect on the welfare of the world than any other Australian. Through his central role in bringing the lifesaving miracle of penicillin to the world, and so ushering in the era of antibiotics, Floret's enduring legacy ranks him as a genuine giant in the world of public health. Without those drugs, millions of people - and countless domestic animals and livestock- would have died or suffered serious illnesses from bacterial infections. It is easy to forget that before antibiotics became available, common infections took an appalling toll on human life. Many infants and mothers died in, or soon after, childbirth; tuberculosis and bacterial pneumonia were often deadly; and one bacterium alone - the infamous golden staph (staphylococcus aureus) - killed eight out of every 10 people infected after sustaining even the slightest wound.

Yet Florey claimed such concerns did not motivate his research. "Peopie sometimes think that I and the others worked on penicillin because we were interested in suffering humanity," he told Hazel be Berg in 1967 (transcript from a taped interview with Lord Howard Florey, April 5 1967, National Library, Canberra). "I don't think it ever crossed our minds · about suffering humanity. This was an interesting scientific exercise, and because it was of some use in medicine is very gratifying, but this was not the reason that we started working on it."

SENSITIVE SCIENTIST

This comment highlights the complexities of the individual behind the legend. His letters and the recollections of friends and colleagues point to a man who was a chain-smoker, inwardly shy, sensitive enough to be moved to tears by a musical performance, unpretentious, self-deprecating and possessed of great integrity. He hated nationalism and was deeply concerned for the plight of the dispossessed and hungry.

Yet he was notorious for being gruff, driven, uncompromising, blunt, overbearing and, at times, callous to others. He once unceremoniously sacked a technician for theft, yet quietly found the man another job. For all his achievement, he humbly attributed much of it to luck and to the hard work of those around him. A long-time colleague once commented that he never heard Florey utter a word in praise of himself. Florey was born in suburban Adelaide on September 24 1989, the only son (he had four older sisters) of Joseph and Bertha Florey. Joseph was widowed when his first wife Charlotte died from tuberculosis but his early business success as a footwear manufacturer meant that Howard had a comfortable start in life. In 1906, his father's growing wealth enabled the family to move into Coreega, a two-storey, 16-room sandstone house in the well-to-do suburb of Mitcham. It was obvious from an early age that the young Florey was an exceptional individual. Between 1908 and 1910, he attended Kyre College preparatory school - now Scotch College - and later St Peter's College. He soon emerged as a genuine all-rounder, with diverse intellectual and physical talents, a strong character with leadership qualities. He won medals in gymnastics, sprinting and hurdles, and he captained tennis, cricket and football teams. At high school he was secretary of the debating society and was made head prefect in 1916. He regularly topped his classes academically and excelled in both science and the humanities, winning prizes in chemistry and history among other awards.

He was inspired by his chemistry teacher - known as Sneaker Thompson - the same man who had earlier sparked the intellect of another outstanding student from the same school who also went on to become a Nobel Laureate: Lawrence Bragg. Florey decided to study medicine at the University of Adelaide in 1917 but in the following year tragedy struck the family: not only did Joseph Florey lose all his wealth when his business failed but he died soon· after of a heart attack. Despite more straitened circumstances, Florey was able to continue his studies with the help of scholarships and he again excelled in sport and academically at university. It was there that he met Ethel Reed, the bright, attractive and outgoing young woman who was to become his wife and a key member of his research team. She had begun studying medicine in 1919 and was the only female in her year. Florey took his final exams in 1921 and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship. He left Australia in December of that year for Oxford University - working his passage as a ship's doctor - where he studied physiology and was awarded a Bachelor of Science degree in 1924. He did not make friends easily, writing home in one letter: "Sometimes I think I am liked here. At others, I get most depressed about it, and revile the English." He knew himself well enough, though, to concede that: "I may not be able to throw off my selfishness and domineering manner." Those doubts were later scotched by his success in forming and leading an exceptional research team. His adventurous spirit saw him join a university expedition to Antarctica in 1924- by repute, the first to fly and crash-land an aircraft on the continent. Switching to Cambridge University, he became a research student and instructor while he completed his doctoral studies.

A Rockefeller Grant in 1925 took him for a time to America, where he rubbed shoulders with prominent scientists and honed his intellect and research skills before returning to Cambridge. All the while he corresponded with Reed, writing more than 150 letters to her up to 1926, when she began working at Royal Adelaide Hospital. Having suffered pleurisy and tuberculosis, she was steadily losing her hearing but their letters at the time reveal that they were discussing marriage. She joined him in England in September 1927, and they were married the following month, a haste that later proved ill-advised since the marriage became a rocky one. Nevertheless, they remained together and had a daughter, Paquita, two years later, and a son, Charles, in 1939. From 1930-34, Florey was Professor of Pathology at Sheffield University and in 1935 he was appointed director of the Sir William Dunn School of Pathology in Oxford, which he came to lead and dominate for the next three decades.

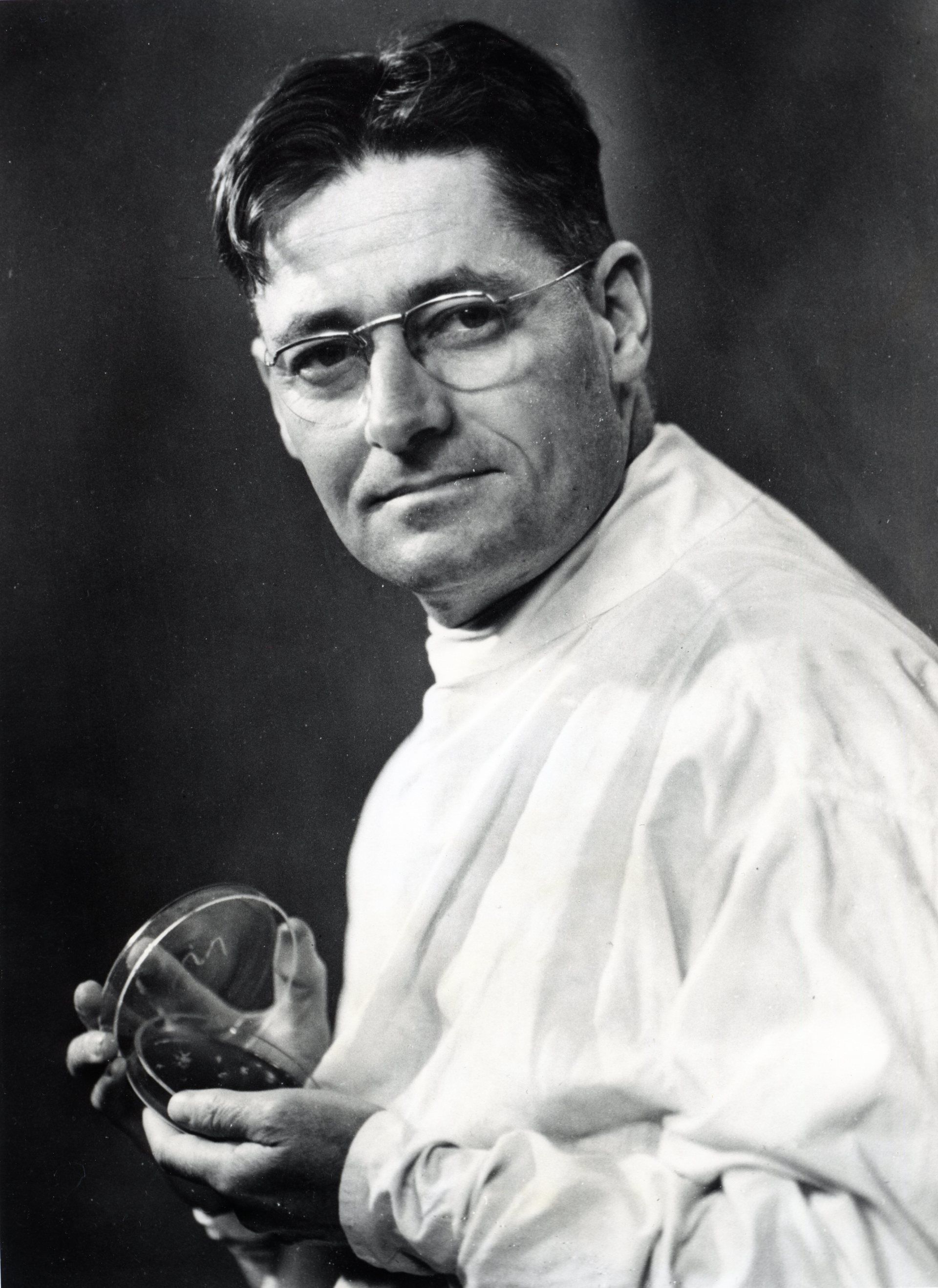

There he began to assemble the team- in itself an unusual approach in those more individualistic days -which would crack the bacterial infection problem. As one of his biographers, the late Robert Gwyn McFarlane (Howard Florey: The Making of a Great Scientist), said: "Florey was a rough, tough Australian, completely uncompromising, rather prickly, very energetic and tense as a coiled spring. And he brought to his work this extraordinary dedication which was very infectious, in such a way that he really could collect a team of people who became almost as dedicated and enthusiastic as himself." Often forgotten behind the drama of the penicillin story is that Florey's other scientific contributions were significant, including important research into immune responses that helped pave the way for vaccination. Indeed, at 43 he had published so many important research papers that he was elected to the prestigious Royal Society in the United Kingdom. Two decades later, Florey was elected its president, the first pathologist and the first Australian to obtain that post. His interest in penicillin was born amid a broader surge of scientific inquiry into the drug-making potential of biological compounds produced by the human body, animals and plants. At Oxford, Florey hired Ernst Chain, a German biochemist, to supplement his own technical skills. Chain was working on snake venom but Florey and others attracted his interest to a substance known as lysozyme, an antibacterial enzyme found in tears and nasal secretions. Together, Chain and Florey decided to systematically survey all known natural antibacterial substances. Among those substances was a simple mould discovered years earlier in London by the Scottish researcher Alexander Fleming, in one of the greatest and most famous pieces of luck in medical research. Fleming returned to his laboratory from a twoweek holiday in 1928 to find that a petri dish with a culture of bacteria left uncovered on his desk had been settled on by a mould spore that had begun to grow to about the size of a 20-cent coin. Around the rim of the mould the bacteria were dead.

MOULDY MUSINGS

At first, Fleming merely noticed the mould then threw it into a bucket. He later retrieved it and tinkered with it experimentally. He had earlier made a study of different antibacterial substances and discovered the antibacterial enzyme lysozyme, so the mould interested him enough to cultivate it. The green mass that grew on the surface of a broth had such a strong effect on bacteria that even when diluted 500 to 800 times, it completely prevented the growth of staphylococci bacteria. It turned out to be a species of the penicillium group of moulds - penicillium notatum -described for the first time only in 1911. Fleming discovered that penicillin was highly effective against many different kinds of bacteria. He performed basic tests on white blood cells and mice to show that it was not toxic and had a little success testing its effect on infected wounds. He published a brief scientific report about it in 1929 but, believing it to be too difficult to work with and not showing enough promise beyond being a possible disinfectant of skin wounds, he moved on.

However, luck again intervened, as Lennard Bickel, a Florey biographer, recalled in a 1998 ABC radio interview. "Chain was reading Fleming's old paper of 15 lines when he had a vision of a woman, one of the ladies who worked at the Dunn School of Pathology, walking along a corridor with a dish in her hand on which a mould was growing. He went to see this lady and said to her, 'This mould that I saw you with... .', she said, 'Yes', he said, 'What is it?' She told him it was penicillium notatum, this species of mould, and he said, 'That is the very mould that Fleming found in 1928'. She said, 'Yes, he cultured it and he gave us a piece of it, and we've kept it alive ever since'. Science is so full of pieces of serendipity.”

In 1938, Florey and Chain began to study the mould more closely and found that it grew slowly and had special needs. They experimented with different growing mixtures, including Marmite, malt extract, meat and yeast extracts and studied its growth rate. They began to work out how to extract the active penicillin compound from the brown juice that accumulated beneath the surface layer of green mould. Funds were short despite Florey's many urgings for more financial support, so in the Australian tradition of making do with whatever materials were to hand, he encouraged his team to experiment with growing the mould in biscuit tins and various dishes and pans. Hospital bedpans turned out to be the best-shaped growing containers.

Old dairy equipment, a letterbox and an aquarium pump were among the items pressed into service to make the first penicillin. It turned out to be highly unstable stuff. The scientists quickly moved on from filtering the juice through parachute silk to a more sophisticated extraction process using solvents. Chain worked out a series of steps to isolate, purify and concentrate the penicillin in the liquid but another member of the team improved the process so that soon they were able to extract and produce penicillin as a brown powder in small but useful quantities. Now the team could experiment with the powder to test its effects. Chain dissolved some in water and injected it into two mice that survived the experience despite its highly impure state.

Working with increasing strengths of the powder, Florey's team tested it on blood, hormones and living cells. The turning point came, however, one morning in May 1940, when Florey injected a lethal dose of streptococcus pyogenes bacteria into eight mice but injected four of them with penicillin as well. The team anxiously watched the mice and by the middle of that night - just 16 hours later - all the unprotected mice were dead while those that had received penicillin remained alive and well. Chain is said to have almost danced with glee and even the understated Florey gave way to excitement when he later called his assistant Margaret Jennings to report the outcome of the experiment and said: "It looks like a miracle". The team duly reported to other scientists that penicillin was a therapeutic agent able to kill sensitive germs in a living body and, with so many people suffering war wounds, the race began to work out ways to make enough of the stuff to test it on people. Not until February 1941 was there sufficient funding to do that. A policeman named Albert Alexander, near death from an infection sustained when he pricked himself on a rose thorn, was selected as the first recipient of penicillin. Within a day, Alexander was showing dramatic signs of recovery but there was no more penicillin available to give him further treatment. Despite heroic efforts to filter his urine to recapture any excreted penicillin, Alexander's infection took hold again and he died. It became apparent that a course of several treatments was needed to thoroughly kill off germs and Florey firmly decided that not until supplies of penicillin were great enough to effect a cure would it be tested on anyone else. With British funds limited due to the war effort, Florey and a colleague took the risk of flying a blacked-out aircraft to the United States a few months later to seek help in boosting production of the drug. Better ways of growing the mould were soon found and another species of it - penicillium chrysogenum- was discovered having infected a cantaloupe melon, by Mary Hunt (an enthusiastic seeker of new moulds known as Mouldy Mary). It turned out to be a much better producer of penicillin. Florey returned to Britain and the first penicillin to be used in a war zone - in Cairo - was administered in 1942. The next year, in belated recognition of the significance of his work, the British Government finally gave Florey's team full funding. His wife Ethel was a vital member of the team during this time, working long hours with Florey on experiments and testing the drug and publishing the results jointly with him.

His laboratory now became a makeshift penicillin factory with teams of workers tending hundreds of jars of mould. By October that year, the first supplies went to the British Army. With better extraction and greater production came increasing success in human use, with most war wounds now being cured of infection. By 1945, enough penicillin was being produced, including by drug companies in the United States and Australia, notably the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories in Melbourne, to take penicillin to the wider community. In 1944, Australia was the first country to offer it for civilian use.

INCREASING RESISTANCE

Within a few years, in a foretaste of today's global problem with antibiotic resistance, several strains of bacteria started to become resistant to natural penicillin and the pharmacological spotlight soon turned to making synthetic forms which were developed in the 1950s and 1960s. Florey's remarkable achievement was quickly recognised. He was knighted by Britain in 1944 and honoured as well by France, the US and Australia for having such an unforeseen but undeniable influence on the course of the war and on medicine. In December 1945, Florey, Chain and Fleming were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for "the discovery of penicillin and its curative effects in various infectious diseases". In 1966, Lady Ethel Florey died at home. In London on June 6 1967, Lord Florey married again, to Dr M~ugaret Jennings, a member of his team and his special assistant for more than three decades. Just eight months later, on February 21 1968, he died in Oxford of a heart attack, aged 69 (Lady Margaret Florey died in 1994). In the eulogy at Westminster Abbey, Lord Adrian said of him: "Florey inspired the research and made it succeed. We have still to adjust our ideas to the extent of the revolution in medical treatment that Florey brought to success." Norman Heatley, a key worker in the Oxford tearp, wrote of Florey's "genius in leading his colleagues and providing at the right times the encouragement, advice, inspiration and realism which kept the team working constructively throughout".

Perhaps the last word should go to one of his friends, Sir Alan Drury, who recalled Florey coming to Britain: "His drive and ambition were manifest almost from the day he arrived. A great fire seemed to burn within him, and his many-sided character was never concealed. We could all see the power in him and wondered whether he would ever find the right outlets for this greatness." Florey recognised that his success was due to a team effort and for this reason he always acknowledged the team in his publications, usually listing them in alphabetical order. He disliked the public spotlight and, unlike Fleming, shunned media attention to the extent that Fleming's name is still far better known for the discovery of penicillin than is Florey's. In his oration speech, Fleming acknowledged the role of luck in his discovery. He said: "My only merit is that I did not neglect that chance observation and pursued it as a bacteriologist. The first practical use was to sort out bacteria that were sensitive from those that were not. We tried to concentrate it but found, as others did later, that it was easily destroyed - and, to all intents and purposes, we failed." In his own oration, Florey lauded his team and its scientific approach, and looked forward to the revolution that penicillin and other probiotics promised to bring. Other scientists followed in his path, discovering new moulds and other types of antibiotics, some of them with the help of Florey's team. In his Nobel Prize presentation speech, professor Goran Liljestrand, of the Royal Caroline Institute, saw Florey's work in stark contrast to the bloody war that had just ended. "To overcome the numerous obstacles, all this work demanded not only assistance from many different quarters but also an unusual amount of scientific enthusiasm and a firm belief in an idea. In a time when annihilation and destruction through the inventions of man have been greater than ever before in history, the introduction of penicillin is a brilliant demonstration that human genius is just as well able to save life and combat disease."

Vital Statistics

Name Howard Walter Florey

Born Adelaide, South Australia

Birthdate September 24, 1898

Died February 21, 1968, Oxford, England

School St Peters College (Adelaide)

University University of Adelaide; Oxford University; Cambridge University

Married Mary Ethel Hater Reed in October 1927, Ethel died in 1966. Married Dr Margaret Jennings in June 1967

Children Paquite, Charles

Lived Mainly in Oxford, England

Awards and Accolades

1935 Professor of Pathology and a Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford

1944 Nuffield Visiting Professor to Australia and New Zealand

1944 Created a Knight Bachelor

1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

1946 Honorary Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

1949 Contributor to, and editor of, Antibiotics. He also had many papers published on physiology and pathology

1952 Honorary Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford

1960 President of the Royal Society (first Australian to be elected)

1962 Provost of the Queen’s College, Oxford

1965 Made Baron Florey of Adelaide and accepted the Chancellorship of the Australian National University that same year.

Other honours include: The Lister Medal of the Royal College of Surgeons, the Berzelius Medal of the Swedish Medical Society, the Royal and Copley Medals of the Royal Society, the Medal of Merit of the US Army, and many others. He was a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians and held on honorary fellowship of the Royal Australian College of Physicians. He has been awarded honorary degrees by 17 universities and was a member or honorary member of many learned societies and academies in the field of medicine and biology.

Why he was awarded the Nobel Prize

Howard Florey, Ernst Chain and Alexander Fleming were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1945 in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effects in various infectious diseases. Penicillin had been discovered by Fleming in 2928 but the active substance was not isolated. In 1939, Florey and Chain headed a team of British scientists, financed by a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation, whose efforts led to the successful small-scale manufacture of the drug from the liquid broth in which it grows. Without penicillin, millions of people would have died or suffered serious illness from bacterial infections.