Mollusks, magnets, and clean steel

Madeleine Achenza

The world’s hardest known biomineral is produced by a sea mollusk, which pulls in iron from the water

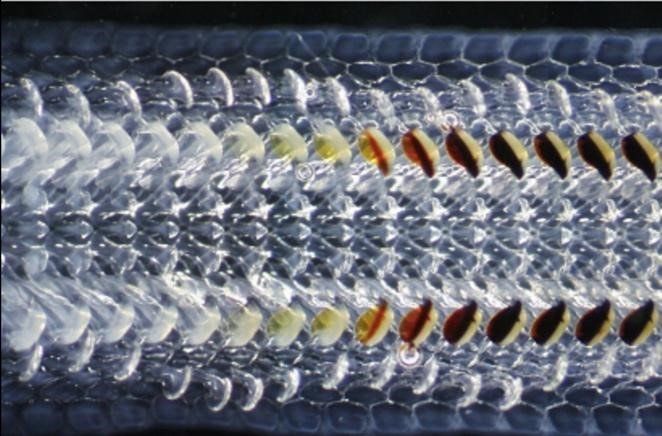

Image courtesy of Jeremy Shaw, University of Western Australia

Using new quantum magnetic imaging techniques, the team was able to understand how the species is able to extract iron from sea water and mineralize it into a tooth coating, made from magnetite, that is stronger than steel.

Dr David Simpson, one of the scientists working on the development of this technology for over a decade, revealed to Innovation Intelligence this week, that this is the first time that the magnetic properties of the animal have been explored with such detail and resolution.

Magnetite is one of the two most common iron-bearing minerals found in iron ore and can also be synthesized in a lab environment, but both methods require intensive procedures including high temperatures and strong acidic chemicals.

Magnetite is already used in a variety of industrial applications - the needle point of a compass, in MRI machines, and in the production of clean steel. Understanding the natural process through which the mollusc mineralizes magnetite would advance the production of abrasion resistant materials and nanoscale materials for energy, such as solar cells and fast charging batteries.

The chiton mollusc found in the inner tidal zones of Australia’s east coast has evolved and optimised the process of magnetite production at temperatures as low as 15-20 °C and without creating excess harmful chemicals.

“What’s amazing about the chiton is that they can just sit in the water, extract iron from the water and start to assemble this material in a much more efficient way, without requiring these complex acids, bases and temperature.

“The structure of these particles is slightly different to what you would create synthetically, and what we’ve seen is that the mollusc outperforms what we can currently make”, said Dr Simpson.

The new microscopy technique is incredibly sensitive to magnetic fields, able to detect one a million times weaker than your standard fridge magnet.

In an article he wrote for Science Matters, Dr Simpson explained that the sensitivity of the imaging has allowed them to pinpoint the exact location of the magnetic field in a specific tooth. This led to the unexpected discovery that magnetic domains are aligned and ordered across the entire tooth section.

“Now we need to consider that there is a magnetic component to the self assembly, which we didn’t know existed before,” explained Dr Simpson.

“We’re not at a point yet where we can dip this in a bucket and start coating drill bits or anything like that,” suggested Dr Simpson. ”I still think that it’s many years away from being able to be scaled up and fully industrial but its certainly a key part of the puzzle.”

Just in the last week, Dr Simpson has already seen industry interest in using the magnetic microscopy to measure magnetite in a number of animal species, some he had not previously considered.

He made note of colleagues in Vienna, that are currently testing the hypothesis that pigeons navigate via the earth’s magnetic field, potentially due to magnetic particles in the bird’s body.

“This technique is perfect for that – its extremely sensitive, so we can detect very weak magnetic fields. We can spatially correlate where that signal is coming from,” said Dr Simpson.

Looking forward, the team of scientists at the University of Melbourne see their magnetic imaging technique as a gateway to revolutionising the cost and efficiency of blood tests for iron related disorders.

“At the moment if you want an accurate assessment of your iron load, you need to get an MRI,” explains Dr Simspon, “and this is a very prohibitive, costly, test.”

He says the clinical test undertaken by general practitioners to test iron levels in blood, doesn’t accurately test magnetic content. This is a problem that they are confident their machine would overcome, given its ability to detect magnetism on the nanoscale.

In 2016 I published a blog article titled Moonshots for Australia: 7 For Now. It’s one of many I have posted on business and innovation in Australia. In that book, I highlighted a number of Industries of the Future among a number of proposed Moonshots. I self-published a book, Innovation in Australia – Creating prosperity for future generations, in 2019, with a follow-up COVID edition in 2020. There is no doubt COVID is causing massive disruption. Prior to COVID, there was little conversation about National Sovereignty or supply chains. Even now, these topics are fading, and we remain preoccupied with productivity and jobs! My motivation for this writing has been the absence of a coherent narrative for Australia’s business future. Over the past six years, little has changed. The Australian ‘psyche’ regarding our political and business systems is programmed to avoid taking a long-term perspective. The short-term nature of Government (3 to 4-year terms), the short-term horizon of the business system (driven by shareholder value), the media culture (infotainment and ‘gotcha’ games), the general Australian population’s cynical perspective and a preoccupation with a lifestyle all create a malaise of strategic thinking and conversation. Ultimately, it leads to a leadership vacuum at all levels. In recent years we have seen the leadership of some of our significant institutions failing to live up to the most basic standards, with Royal Commissions, Inquiries and investigations consuming excessive time and resources. · Catholic Church and other religious bodies · Trade Unions · Banks (and businesses generally, take casinos, for example) · the Australian Defence Force · the Australian cricket teams · our elected representatives and the staff of Parliament House As they say, “A fish rots from the head!” At best, the leadership behaviour in those institutions could be described as unethical and, at worst….just bankrupt! In the last decade, politicians have led us through a game of “leadership by musical chairs” – although, for now, it has stabilised. However, there is still an absence of a coherent narrative about business and wealth creation. It is a challenge. One attempt to provide such a narrative has been the Intergenerational Reports produced by our federal Government every few years since 2002. The shortcomings of the latest Intergenerational Report Each Intergenerational Report examines the long-term sustainability of current government policies and how demographic, technological, and other structural trends may affect the economy and the budget over the next 40 years. The fifth and most recent Intergenerational Report released in 2021 (preceded by Reports in 2002, 2007, 2010 and 2015) provides a narrative about Australia’s future – in essence, it is an extension of the status quo. The Report also highlights three key insights: 1. First, our population is growing slower and ageing faster than expected. 2. The Australian economy will continue to grow, but slower than previously thought. 3. While Australia’s debt is sustainable and low by international standards, the ageing of our population will pressure revenue and expenditure. However, its release came and went with a whimper. The recent Summit on (what was it, Jobs and Skills and productivity?) also seems to have made the difference of a ‘snowflake’ in hell in terms of identifying our long-term challenges and growth industries. Let’s look back to see how we got here and what we can learn. Australia over the last 40 years During Australia’s last period of significant economic reform (the late 1980s and early 1990s), there was a positive attempt at building an inclusive national narrative between Government and business. Multiple documents were published, including: · Australia Reconstructed (1987) – ACTU · Enterprise Bargaining a Better Way of Working (1989) – Business Council of Australia · Innovation in Australia (1991) – Boston Consulting Group · Australia 2010: Creating the Future Australia (1993) – Business Council of Australia · and others. There were workshops, consultations with industry leaders, and conferences across industries to pursue a national microeconomic reform agenda. Remember these concepts? · global competitiveness · benchmarking · best practice · award restructuring and enterprising bargaining · training, management education and multiskilling. This agenda was at the heart of the business conversation. During that time, the Government encouraged high levels of engagement with stakeholders. As a result, I worked with a small group of training professionals to contribute to the debate. Our contribution included events and publications over several years, including What Dawkins, Kelty and Howard All Agree On – Human Resources Strategies for Our Nation (published by the Australian Institute of Training and Development). Unfortunately, these long-term strategic discussions are nowhere near as prevalent among Government and industry today. The 1980s and 1990s were a time of radical change in Australia. It included: · floating the $A · deregulation · award restructuring · lowering/abolishing tariffs · Corporatisation and Commercialisation Ross Garnaut posits that the reforms enabled Australia to lead the developed world in productivity growth – given that it had spent most of the 20th century at the bottom of the developed country league table. However, in his work, The Great Reset, Garnaut says that over the next 20 years, our growth was attributable to the China mining boom, and from there, we settled into “The DOG days” – Australia moved to the back of a slow-moving pack! One unintended consequence of opening our economy to the world is the emasculation of the Australian manufacturing base. The manic pursuit of increased efficiency, lower costs, and shareholder value meant much of the labour-intensive work was outsourced. Manufacturing is now less than 6% of our GDP , less than half of what it was 30 years ago!