Public-private partnerships that benefit all

Rob Adams – City Design, City of Melbourne

Over the past 25 years the City of Melbourne has used public-private partnerships (PPPs) to deliver real value to their community. The nature of these partnerships has kept true to the original principle of PPPs, that all parties should benefit from the partnership.

Unfortunately, PPPs have more recently acquired a bad reputation as they have been used by governments as a mechanism to delay payments and defer risks, costing the public more over the long term. A new development of this approach is the private sector-led proposal, whereby the private sector pitches proposals to government so avoiding any real competition in the process

There are consistent themes that make the City of Melbourne PPPs different:

- All of the proposals were led from within Council by an in-house team of experts.

- The City contributed to the partnership by using its existing, or recently acquired assets.

- The City shared in the risk but put in place mechanisms to ensure this risk was managed and reasonable. This usually meant the City retained equity in the process until the risk was minimised.

- The process of finding a partner was always competitive, with quality design and public benefit high on the selection criteria.

- The City acted as an intelligent client through its in-house team, and recognised that successful partnerships take time to deliver and implement, often bridging two terms of office by the Councillors.

- The City started small and built confidence internally, and with the development industry.

- The partnerships needed to be well aligned with the Council’s goals, such as affordable housing, sustainability, and repair of the city fabric. These goals had been established in the City of Melbourne’s 1985 Strategy Plan which sought to:

- bring back people to live in the city, so adding density and mixed use;

- favour pedestrians and public transport over cars, so improving connectivity while giving back more space to people;

- remove all surface-level carparks, so ensuring an excellent street experience with a high-quality public realm that favoured walking;

- build on the city's physical attributes – its local character such as the laneways, bluestone and high-quality open spaces.

In the late 80s, when the PPP program started, the City had limited finances, and while there were funds for the basics, the more ambitious projects needed partners in order to be realised. The first two projects were reasonably conventional:

Cafe L’Incontro

A small open space on the corner of Little Collins and Swanston Streets was populated by more pigeons than people. The plan was to design, in-house, a small café elevated above the public space, providing a comfortable place to sit overlooking the recently pedestrianised Swanston Street. The cafe provided an active edge to the space, which was contained by an Akio Makigawa sculpture . The concept was put to the market in 1993/94 on the basis that the successful team would secure a lease over the site - in this case, 30 years - after which the development would revert to the City.

Tyne Elgin Street Carpark

The property was a surface-level carpark that accommodated an old house and 110 parking spaces. The proposal was to go to market for an underground carpark with 215 short-stay spaces. The strata above the slab would be for residential development. A special requirement was that the final development should reinstate the two laneways that had been compromised by the demolition to form the existing surface carparking. The City achieved all its requirements, with the extra parking welcomed by the retailers, and the repaired neighbourhood liked by the local residents. The City retained a quality carpark which has returned steady revenue for over 20 years.

The City Square

Similar to Tyne Elgin but on a grander scale that involved a land swap by the City. This allowed the building of a hotel and residential development which provided active frontages and passive surveillance of the square, a new laneway, 400 underground short-stay parking spaces, a new, softer City Square and the refurbishment of the historic Regent Theatre.

QV Melbourne

With the success of these three projects the City became more ambitious and following concern about the proposed development on the Queen Victoria Hospital site in Swanston Street in 2000, the City purchased the site from the Nauru government for $35m in order to determine the outcome. It then packaged a brief that required the developers to provide an underground supermarket to support the city’s rapidly increasing residential population, 2000 short-stay parking spaces to help the retailers and hospitality area of Chinatown, lanes and arcades with small tenancies and complete active frontage, and a childcare facility. It also required that the development should not be designed by a single architect but rather be a campus style development with multiple hands. The result was the QV development which helped turn around the declining retail in the CBD. The City returned a modest profit of $3.5m from interest earned by leaving its money in the development while retaining the land title until practical completion.

QVM Precinct Renewal

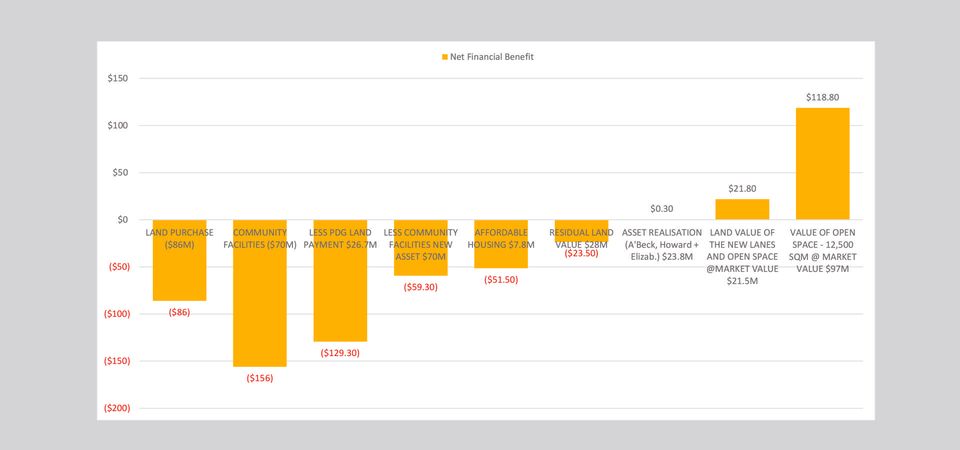

The most recent example, currently under construction, is the Munro site in Therry Street opposite the Queen Victoria Market. This forms part of a larger precinct and the QVM Precinct Renewal but is a crucial site. It will allow the City to remove surface level carparking, and place the parking underground, thus allowing for the creation of a circa 1.75-hectare Market Square. It also allowed the City to support retail at the market and avoid the introduction of a supermarket and chain stores. The successful developer is providing 15% affordable housing, building community facilities, including 120 space childcare, and providing lanes and open space. The safeguard built in for the City was that the developer was required to build the 500-space carpark and the community facilities before gaining title. The best way to explain the public benefit is in the waterfall chart below.

JH Boyd School

This Munro model has been repeated at the former JH Boyd School in Southbank where the City purchased the site for $10.5m, built in a library for $7m, and an open space for $4m, selling off a small parcel of land to a developer on the requirement that it provide 15% affordable housing and 1000 square meters of community space, all at a 6 Star Green Star rating. The price paid by the developer paid off all the previous investments and left the City with a residual site value of $23m.

Postcode 3000

Arguably, the most successful PPP carried out by the City was Postcode 3000. The program saw the inner city increase the number of its residential units from 650 in 1985 to nearly 50,000 today, so producing the single biggest change to the central city since the 19th century gold rush.

The secret to these kinds of projects is that Councils need to retain the in-house expertise that allows them in the first place to conceive of the projects, and then have the skills to negotiate and manage the risk of delivery. The City of Melbourne has done this for 30 years, and its communities continue to benefit from these actions while their credibility within private enterprise remains high.

This piece is taken from our upcoming book, Australia's Nobel Laureates, Vol. III, celebrating Australian science and innovation. Taking a whole-of-economy healthcheck on Australia's innovation ecosystem, the book features words from industry, academia, and Government.

In 2016 I published a blog article titled Moonshots for Australia: 7 For Now. It’s one of many I have posted on business and innovation in Australia. In that book, I highlighted a number of Industries of the Future among a number of proposed Moonshots. I self-published a book, Innovation in Australia – Creating prosperity for future generations, in 2019, with a follow-up COVID edition in 2020. There is no doubt COVID is causing massive disruption. Prior to COVID, there was little conversation about National Sovereignty or supply chains. Even now, these topics are fading, and we remain preoccupied with productivity and jobs! My motivation for this writing has been the absence of a coherent narrative for Australia’s business future. Over the past six years, little has changed. The Australian ‘psyche’ regarding our political and business systems is programmed to avoid taking a long-term perspective. The short-term nature of Government (3 to 4-year terms), the short-term horizon of the business system (driven by shareholder value), the media culture (infotainment and ‘gotcha’ games), the general Australian population’s cynical perspective and a preoccupation with a lifestyle all create a malaise of strategic thinking and conversation. Ultimately, it leads to a leadership vacuum at all levels. In recent years we have seen the leadership of some of our significant institutions failing to live up to the most basic standards, with Royal Commissions, Inquiries and investigations consuming excessive time and resources. · Catholic Church and other religious bodies · Trade Unions · Banks (and businesses generally, take casinos, for example) · the Australian Defence Force · the Australian cricket teams · our elected representatives and the staff of Parliament House As they say, “A fish rots from the head!” At best, the leadership behaviour in those institutions could be described as unethical and, at worst….just bankrupt! In the last decade, politicians have led us through a game of “leadership by musical chairs” – although, for now, it has stabilised. However, there is still an absence of a coherent narrative about business and wealth creation. It is a challenge. One attempt to provide such a narrative has been the Intergenerational Reports produced by our federal Government every few years since 2002. The shortcomings of the latest Intergenerational Report Each Intergenerational Report examines the long-term sustainability of current government policies and how demographic, technological, and other structural trends may affect the economy and the budget over the next 40 years. The fifth and most recent Intergenerational Report released in 2021 (preceded by Reports in 2002, 2007, 2010 and 2015) provides a narrative about Australia’s future – in essence, it is an extension of the status quo. The Report also highlights three key insights: 1. First, our population is growing slower and ageing faster than expected. 2. The Australian economy will continue to grow, but slower than previously thought. 3. While Australia’s debt is sustainable and low by international standards, the ageing of our population will pressure revenue and expenditure. However, its release came and went with a whimper. The recent Summit on (what was it, Jobs and Skills and productivity?) also seems to have made the difference of a ‘snowflake’ in hell in terms of identifying our long-term challenges and growth industries. Let’s look back to see how we got here and what we can learn. Australia over the last 40 years During Australia’s last period of significant economic reform (the late 1980s and early 1990s), there was a positive attempt at building an inclusive national narrative between Government and business. Multiple documents were published, including: · Australia Reconstructed (1987) – ACTU · Enterprise Bargaining a Better Way of Working (1989) – Business Council of Australia · Innovation in Australia (1991) – Boston Consulting Group · Australia 2010: Creating the Future Australia (1993) – Business Council of Australia · and others. There were workshops, consultations with industry leaders, and conferences across industries to pursue a national microeconomic reform agenda. Remember these concepts? · global competitiveness · benchmarking · best practice · award restructuring and enterprising bargaining · training, management education and multiskilling. This agenda was at the heart of the business conversation. During that time, the Government encouraged high levels of engagement with stakeholders. As a result, I worked with a small group of training professionals to contribute to the debate. Our contribution included events and publications over several years, including What Dawkins, Kelty and Howard All Agree On – Human Resources Strategies for Our Nation (published by the Australian Institute of Training and Development). Unfortunately, these long-term strategic discussions are nowhere near as prevalent among Government and industry today. The 1980s and 1990s were a time of radical change in Australia. It included: · floating the $A · deregulation · award restructuring · lowering/abolishing tariffs · Corporatisation and Commercialisation Ross Garnaut posits that the reforms enabled Australia to lead the developed world in productivity growth – given that it had spent most of the 20th century at the bottom of the developed country league table. However, in his work, The Great Reset, Garnaut says that over the next 20 years, our growth was attributable to the China mining boom, and from there, we settled into “The DOG days” – Australia moved to the back of a slow-moving pack! One unintended consequence of opening our economy to the world is the emasculation of the Australian manufacturing base. The manic pursuit of increased efficiency, lower costs, and shareholder value meant much of the labour-intensive work was outsourced. Manufacturing is now less than 6% of our GDP , less than half of what it was 30 years ago!