Rear Admiral (Rtd) Michael Julian van Balen AO was appointed Principal of the Australian Maritime College in 2019. Career highlights include Commanding Officer of HMAS Sydney (FFG-03) in 2003, where he deployed to the Persian Gulf for the war in Iraq.

No Modern Nation Can Thrive Without Engineers

Rear Admiral (Retd) Michael Julian van Balen AO, Principal of the Australian Maritime College, discusses the persistent shortage of STEM skilled graduates and declining STEM talent pool. With Australia’s maritime security at stake, he calls for a whole-of-nation response.

At the opening of a science facility in Canberra in 1988, the then Prime Minister, the late Bob Hawke, agreed that Australia needed to become “the clever country”. At that time, Australia could still benefit from technological, economic, social, and political innovations that were developed in other countries.

In 2015, the then Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, challenged us to become the ‘innovation nation’. Today, we are far behind on numerous metrics: and the changing geo-political, natural, and economic environment in which we find ourselves, shows we are not as far away from the problems of the world as we once were.

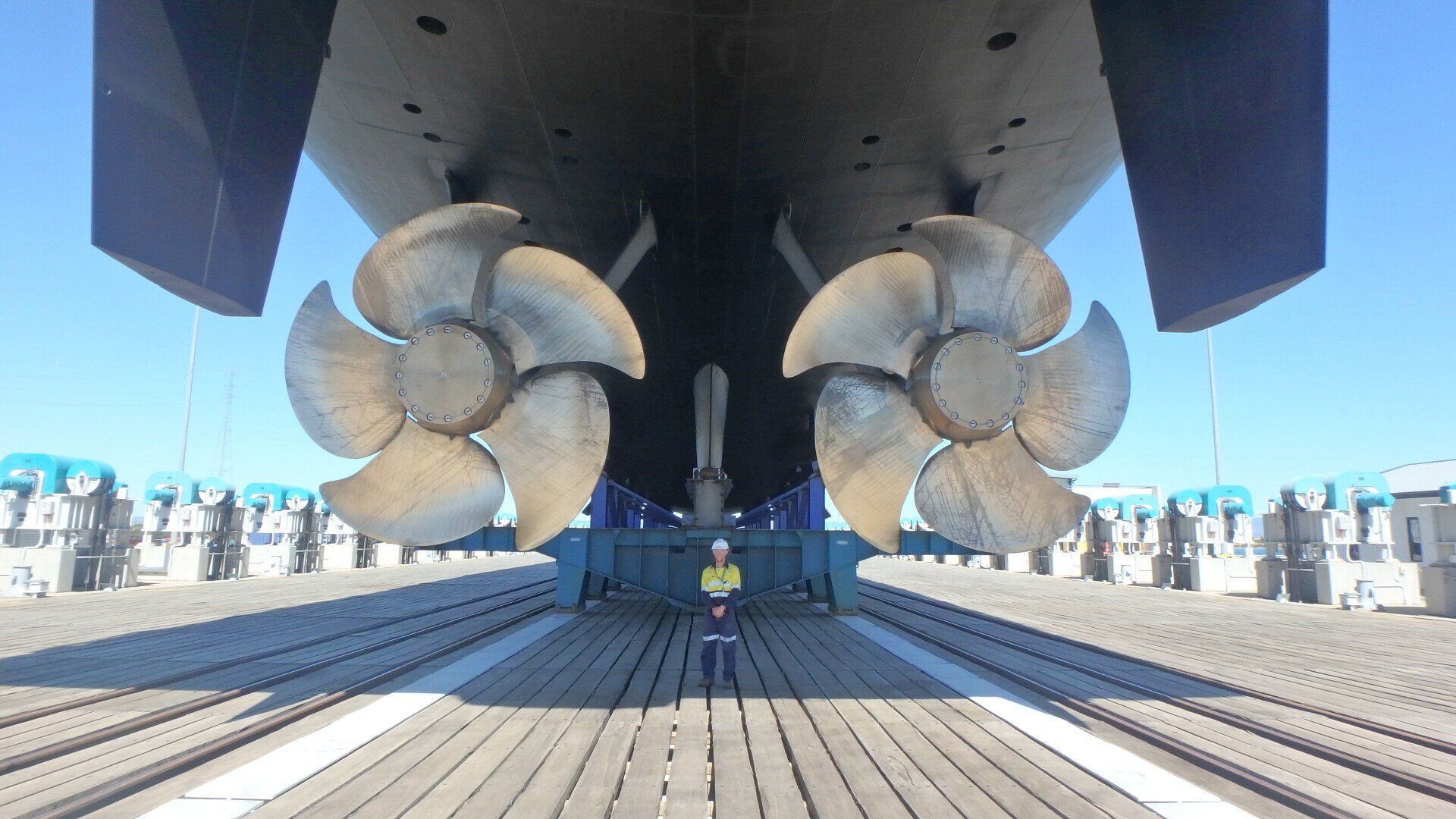

As a maritime nation, Australia is reliant on the sea for trade, resources, security, and economic prosperity, though the importance of the maritime ecosystem as historically languished in the national psyche. More than a generation since Hawkes’ “clever country” declaration, recent regional and global geo-political events and the COVID-19 pandemic have raised our consciousness on the importance of being an Indo-Pacific maritime nation. This is evidenced by the Federal government’s naval shipbuilding program, proposed acquisition of nuclear submarines, and discussion on development of a “strategic” (merchant) fleet.

Our ability to develop the industrial complex to fulfil these strategic plans is, however, hampered by past inactivity, inefficiencies in the high cost of manufacturing, and ongoing cultural reluctance to develop the necessary science, technology, engineering, and maths (STEM) skills.

As a nation, we more than ever need to become highly educated and skilled, efficient, cost competitive, and innovative. We must become the “clever” country to ensure our strategic plans and future security and prosperity are not at risk.

NINETY EIGHT PERCENT OF AUSTRALIA’S TRADE BY SEA

Australia conducts 98 percent of its trade by sea; therefore, most domestic economic activity and employment is reliant on this trade. In 2018-19, Australia imported $239.0 billion of goods by sea, and exported $333.8 billion worth. In 2017-18, the economic output of the Australian maritime industry, including natural gas, LPG, oil, fisheries, shipbuilding and repair, marine equipment, and water-based tourism and transport was $81.2 billion; and it provided employment for nearly 340,000 full time workers. Yet, most Australians are oblivious to the importance of the maritime ecosystem.

The rise of China and its claims to the South China Sea, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the decline of the United States’ hegemony have challenged the world order, and the rule of law, and woken us to the importance of the maritime.

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT RECOGNITION OF SEVERE SHORTFALL

The Federal government has committed over the next 30 years to a $183 billion continuous Naval Shipbuilding Plan, with additional funding for a nuclear submarine program expected to be announced in early 2023. At the same time, the veil has been lifted on the indigent state of Australia’s national merchant fleet which has reduced from approximately 100 vessels three decades ago, to just 14 today. The government has now recognised the reliance we place on foreign governments and companies for our essential imports, a reliance which has been exacerbated in recent times by the COVID-19 pandemic and natural disasters.

As a result, a taskforce has been established to investigate development of an Australian “strategic fleet” to strengthen our economic sovereignty and national security, and to secure our ongoing access to fuel supplies and other essential imports.

In recognition of the importance of workforce development to delivering the government’s programs, the Naval Shipbuilding College (NSC) was established to support defence industry job seekers and provide advice on opportunities to upskill through direct connections with education and training providers.

NOT THE CLEVER COUNTRY

However, the work of the NSC is occurring in an environment in which the maritime industry, is struggling to recruit. Part of this problem comes from competition with other national infrastructure programs, and the mining and energy industries.

But the biggest negative impact is the apparent reluctance of young Australians to develop the STEM skills required to contribute to the workforce. The number of students studying STEM subjects in Years 11 and 12 has flatlined at around 10 percent; and school students’ science and maths results are declining or stagnant. The impact of this STEM deficiency from a strategic maritime perspective, is most evident in our engineering capability.

Australia has a shortage of engineering skills with only 8.2 per cent of graduates in Australia graduating with an engineering qualification. This compares poorly to countries like Germany at 24.2 per cent, and Japan at 18.5 per cent. In 2022, the top ten engineering disciplines in demand in Australia included civil, mechanical and marine engineers.

Maritime engineers, comprising naval architects, ocean engineers, and marine and offshore engineers, are categorised by Engineers Australia within civil and mechanical engineering areas of practice, and therefore the ability of our workforce to meet the requirements of the national shipbuilding programs is clearly an emerging problem.

A NATIONAL PROBLEM REQUIRES A WHOLE OF NATION RESPONSE

Maritime engineers are also crucial to maritime civil engineering tasks supporting port and offshore mining and energy infrastructure. Immigration policies to assist workforce development are helpful, but in areas such as the nuclear submarine program, for national security reasons, the workforce must be Australian. As such, resolving the workforce challenges in pursuit of our national strategic plan will require collaboration between all levels of government, industry, the tertiary education sector, and professional associations; a willingness and enthusiasm to participate in the pursuit of knowledge and skills by all Australians; and an efficiency and commitment about our purpose.

A whole of nation approach is required to develop skills and to ensure our ongoing economy and prosperity, using all components of our industrial and societal complexes. As a nation, we need to become more educated and skilled, more efficient, more cost competitive, and more innovative. We truly need to become a “clever” country and an “innovative nation”, and this need becomes ever more pressing and challenging the longer we wait to take credible action. So, what are we waiting for?